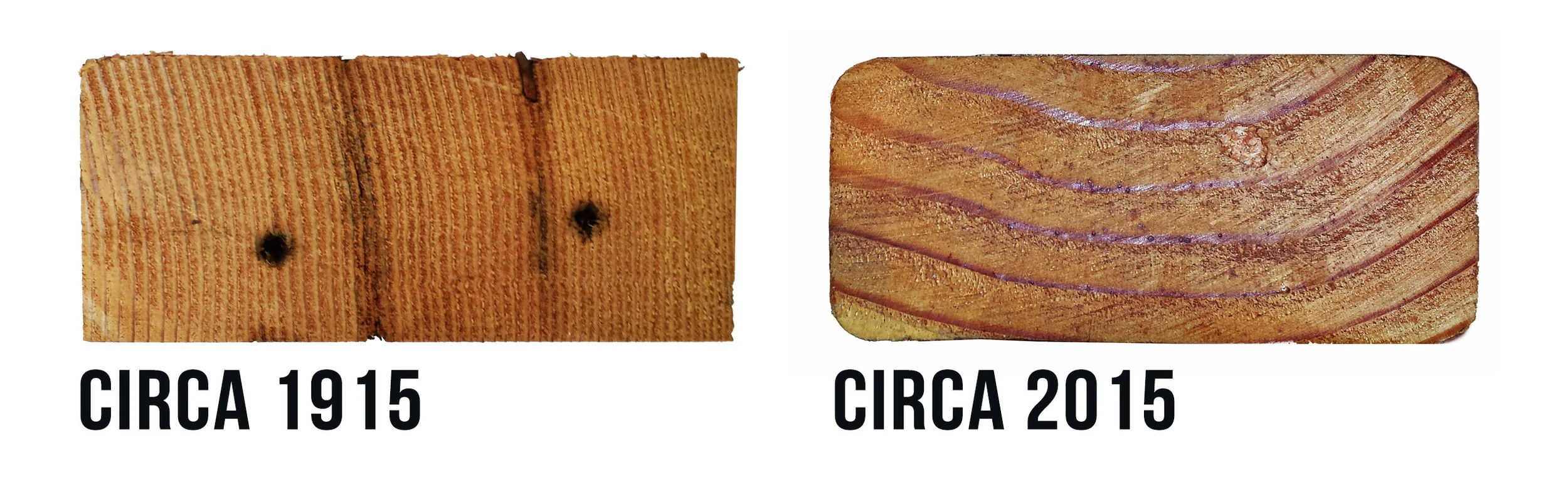

Framing lumber is graded and specified by the amount of weight it can carry over a given span. It is designed to counter the overturning forces of bending moment, failure through shear and deflection. As previously discussed, the quality of currently available framing lumber is not what it used to be. The best commonly available grade of framing lumber is ‘No. 2’, with ‘Select Structural’ and ‘No. 1' grades virtually non-existent. Regular framing lumber is also subject to warping and twisting, and there isn’t a job site in America that doesn’t have mold on some of the new framing members.

To combat this – the lumber industry giant, Weyerhauser, has for the past several years been producing computer-inspected, mechanically graded dimensional lumber. Their M-12 grade lumber, known commonly as the Framer Series, is available locally and has recently found its way into our specifications. Guaranteed by Weyerhauser not to warp, the common concerns associated with dimensional lumber of creaky floors or cracked drywall are assuaged. In addition to this guarantee, Weyerhauser applies a mold inhibitor to the lumber.

The Framer Series lumber is an excellent alternative, in our opinion, to engineered wood I-joists. One of the primary values of wood I-joists (eg TJIs) is their lack of susceptibility to movement and warp, and because of this, they’ve taken over the market. Unfortunately, while they can be designed into fire-rated assemblies and the thin vertical plywood web will last long enough to get occupants out, I don’t think it makes for a safe floor for firefighters to enter on to. Framer Series lumber is true dimensional material, and is suitable for all such fire-rated assemblies. Dimensional lumber isn’t going to last forever in a fire, but I would suspect it would last longer than the web of an I-joist. Also, while I-joists can be designed to meet bending, shear and deflection criteria they can still result in a somewhat springy floor. This is not the case with dimensional lumber. And while Framer Series comes at a cost premium over regular dimensional lumber (ranging from 20-50% more than similarly sized No. 2 Doug Fir), it prices out at less than half the cost of TJIs sized to result in optimal floor performance (from a springiness perspective).